Troubled Times

Natura Naturans n. 9

QUANDO – DOVE / WHEN – WHERE

SEPTEMBER 3 > OCTOBER 16, 2004

Civico Museo di guerra per la pace/Civic War’s Museum for the peace “Diego de Henriquez” via Cumano, 24. Trieste

SEPTEMBER 24 > NOVEMBER 10, 2004

Galleria/Gallery LipanjePuntin via Diaz 4_Trieste

CURATORE / CURATOR

Maria Campitelli

PROMOZIONE E ORGANIZZAZIONE / PROMOTER AND ORGANIZATION

GRUPPO 78 I.C.A., Trieste

con la collaborazione dell’Assessorato alla cultura del Comune di Trieste / with the cooperation of the Cultural Department of Commune of Trieste

SEGRETERIA / SECRETARY OFFICE

Elisa Vladilo

CONTATTI INTERNAZIONALI / INTERNATIONAL CONTACTS

Gruppo 78, Elisa Vladilo

UFFICIO STAMPA / PRESS OFFICE

Vanna Coslovich

IMMAGINE / ART DIRECTOR

Sabina Bonfanti

ALLESTIMENTI / EXHIBITION DESIGN

Elena Carlini & Piero Valle

con / with Plan9 e / and Zeno Petrovich

SUPPORTO TECNOLOGICO / TECHNOLOGICAL SUPPORT

Video New, Trieste

ASSICURAZIONI / INSURANCES

Assicurazioni GENERALI S.p.A.

CATALOGO A CURA DI / CATALOGUE BY

Maria Campitelli

TESTI / TEXTS

Maria Campitelli

Predrag Matvejevic

Melita Richter Malabotta

Fabio Polidori

PROGETTO GRAFICO / LAYOUT

Sabina Bonfanti

TRADUZIONI / TRANSLATIONS

Erik Schneider

FOTOGRAFIE / PHOTOS

Marino Ierman

COPERTINA / COVER

Blood Rain di Robert Gligorov, courtesy LipanjePuntin (TS), Pack (MI)

SUPPLEMENTO AL / SUPPLEMENT TO

n. 119 di JULIET

Aut. Trib. Di Trieste n. 581 del 5.XII.1980

Dir. Resp. Fabio Amodeo

Trieste, ottobre 2004

FOTOCOMPOSIZIONE / PHOTOCOMPOSITION

Millo

STAMPA / PRINTING

Graphart S.n.c. Trieste

Julietart.net

L’ORGANIZZAZIONE DESIDERA RINGRAZIARE PER LA LORO GENTILE COLLABORAZIONE / THE ORGANIZATION WISH TO THANK FOR THEIR KIND COOPERATION

La direzione dei civici Musei di Storia ed Arte di Trieste e in particolare la direzione del Civico Museo di Guerra per la pace / The Direction of History and Art Civic Museums of Trieste and particularly the Direction of Civic War’s for the peace Museum/“Diego de Henriquez”.

Le gallerie / the galleries: Massimo Minini, Brescia; Il Planetario, Trieste; LipanjePuntin, Trieste; Marco Noire, Torino; O’artoteca, Milano; Claudio Poleschi; Lucca; Pack, Milano; Gregor Podnar, Kranj/Lubiana; Jiri Svestka, Praga; Studio Tommaseo, Trieste.

I collezionisti Giuseppe Calvi e Antonio Sibilla.

Il Teatro Miela per il supporto tecnico / Miela Theater for the technical support.

ED INOLTRE/MOREOVER

Adriano Dugulin, Fabiola Faidiga, Roberta Giacomini, Luciano Panella, Giorgio Potocco, Filippo Marini, Sergio Romanelli, Amanda Vertovese.

LA MOSTRA È STATA REALIZZATA CON IL CONTRIBUTO DI:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comune di Trieste

Assesorato alla cultura |

Regione Autonoma

Friuli Venezia Giulia Assesorato alla cultura |

Fondazione CRTRIESTE

|

Assicurazioni Generali

|

Agenzia di informazione e di accoglienza turistica

|

![]()

Troubled Times (di Maria Campitelli)

Maria Campitelli – Troubled Times

I tempi sono duri; dall’11 settembre 2001 le cose nel mondo sono cambiate, il terrore, alimentato da divari culturali, religiosi, economici, sociali, nonché da biechi interessi materiali, dilaga e condiziona la nostra vita. Ma altre radicali trasformazioni sommuovono il pianeta, dalla globalizzazione, con le sue insospettate interazioni nelle parti più disparate del mondo, all’invasione tecnologica, dalle migrazioni dei popoli, alla parcellizzazione di ogni tipo di struttura sia essa urbana, territoriale/abitativa, e persino, in tutt’altro campo, del sistema di guerra, tramutata in guerriglia. Lo stato di guerra è una delle componenti che più scuotono e travagliano l’umanità, nonostante l’universale aspirazione alla pace. Sembra che un perenne scontro negativo attraversi le strade del mondo (basti pensare alla guerra dei Balcani, per restare in Europa, e alle difficoltà della ristrutturazione) e che “il sonno della ragione” – di goyesca memoria – continui a generare i suoi mostri minacciosi, sovvertendo l’ordine delle cose, intaccando l’equilibrio dell’eco-sistema.

E pure la condizione della donna, e non solo nei paesi islamici, rappresenta un nodo fondamentale della negatività congiunturale nonostante l’emancipazione promossa ed attuata nelle battaglie femministe dell’emisfero occidentale, e l’abuso dei minori, in una generale violenza che sembra caratterizzare questi tempi smagati; la disuguaglianza socio-economica, per cui meno del 20 % della popolazione mondiale gode del benessere mentre la maggioranza soffre la fame e non fruisce in modo adeguato dei beni primari quali l’acqua, le ingiustizie, l’accentramento oligarchico del potere che ignora la volontà delle masse, e l’elenco potrebbe continuare.

Troubled Times, nel cogliere il generale disagio, vuole verificare come l’artista reagisca a questa costante alterazione degli equilibri, all’innovazione permanente, sotto certi aspetti, e alle difficoltà di assestamento che ne conseguono, alla precarietà esistenziale rilevabile ovunque in questa congiuntura storica.

Qual è la consapevolezza dell’artista nei confronti di tutto ciò, la sua responsabilità ed il fondamento etico che lo guida, rispetto ai mutamenti epocali che sconvolgono il pianeta? L’artista è già di per sé rivoluzionario e la storia delle avanguardie lo testimonia; non si allinea, se non costretto, ai dettami dei potenti, reagendo anzi alle imposizioni e alle situazioni di regime, con la provocazione, l’ironia, la critica, la satira, la denuncia, diretta o larvata, nell’ancestrale clima di libertà che contraddistingue l’arte.

Del resto le recenti grandi manifestazioni d’arte internazionale, come le Biennali – sia quelle veneziane sia le innumerevoli altre disseminate nel mondo – testimoniano la frequente presa di posizione dell’artista – che oggi spesso ama aggregarsi ad altre forze creative/produttive – nei confronti dei mutamenti socio-culturali, individuando a volte ipotesi alternative allo stato di disagio e di conflitto.

In particolare l’ultima Biennale di Venezia, nella sua caotica impostazione, nella continua apertura verso il documento piuttosto che verso l’opera tradizionalmente intesa, ha largamente soddisfatto questo percorso. Specie la sezione intitolata ”Zone d’urgenza” che affrontava direttamente il diffuso stato di decostruzione e riorganizzazione esistente a vari livelli nelle società attuali.

L’urgenza di sciogliere congiunture desuete e ricostruirle in fretta, in aree circoscritte ed autonome, specie in situazioni metropolitane dell’Est asiatico, sta ad indicare, come evidenzia il curatore della sezione Hou Hanrou, la necessità del cambiamento parcellare in un contesto caotico, nell’interazione tra resistenza e innovazione. Jota Castro, un artista presente a Troubled Times, vi aveva partecipato col suo “Survival guide for demonstrators”(guida di sopravvivenza per dimostranti). Gli artisti dunque, come i pacifisti, come certi movimenti politici fuori dai binari precostituiti dei partiti, percorrono una loro strada di dissenso, impiegando la forza dirompente e privilegiata dell’invenzione, della libera espressione che si avvale delle tecnologie più avanzate come degli iter tradizionali.

Laddove c’è un freno alla libertà, un’ipotesi di condizionamento regimentario, l’arte da sempre si è ribellata, auspicando la caduta di paletti e confini, credendo fermamente nella necessità di aperture, non di chiusure, nella comunicazione innanzi tutto che costituisce la sua stessa natura.

Anche gli artisti di Troubeld Times denunciano, evidenziano, espongono situazioni spesso senza commentarle, perché si commentano da sole, analizzano, producono metafore, ironizzano, scendono perfino sul terreno del gioco, come “The magic war in a Wonderful World” di Massimo Poldelmengo, dove il titolo contiene un’eco di una canzone di Louis Armstrong e rimandi filmici. I soldatini, le armi giocattolo, lo splendore cromatico, trasformano la negatività della guerra in una delicata kermesse spettacolare, con la complicità di sofisticate alchimie tecnologiche sono-visive. Oppure, su di un versante opposto, si raggiunge la sublimazione della morte nel video “Cleaning the mirror” di Marina Abramovic. Nel ritmo pulsante del respiro dell’artista e nel progressivo avvicinamento del suo viso assieme al teschio che su di lei grava, esso anticipa e riassume il senso struggente ed ossessivo, macabro e realistico di Balkan Baroque, la performance indimenticabile della Biennale del ’97, suggello emblematico della guerra dei Balcani.

La guerra è certo un cardine di questa mostra e gli artisti vi si accostano nei modi più disparati. L’iracheno Al Fadhil la condensa nella gigantografia di un unico proiettile, allungato ed elegante, un levigato oggetto di lucido design, perfettamente rispondente allo storico assioma “Form follows the function”.

Un altro proiettile, in video-proiezione, ruota all’infinito, accompagnato da un testo recitato significativo quanto accorato. Si collega, allusivo ed inderogabile, a “Le sette svolte” di Marco Vaglieri. Ossia sette coppie di fotografie dove si associano immagini di residui della I° guerra mondiale e pensieri poetici che denunciano, nella sequenza temporale della settimana e delle stazioni della via Crucis, il concetto fondamentale di perdita, e di disfacimento generati dal potere distruttivo della guerra.

Il video costituisce la prima parte de “Il tempo che serve”, una trilogia che è un’amara riflessione sull’essenza della guerra, condotta analiticamente su antiche testimonianze ricercate nei luoghi – il Carso – dove i tragici fatti sono accaduti.

Memoria, rievocazione, racconto dal ritmo pacato e malinconico, penetrazione del passato per proiettarlo sul presente, si ritrovano nel video “Casa Gatti 44-03” di Gianmaria Conti. Esso ricostruisce un truce episodio di rappresaglia nazi-fascista nei confronti di un gruppo di partigiani attestati in Casa Gatti, nel Modenese, documentando semplicemente i luoghi, esterni ed interni (questi ultimi rimasti immutati dal ’44) in cui si è verificato l’eccidio. Solo alcuni spari in lontananza, verso la .ne, ci riportano alla efferata violenza allora perpetrata. Il lavoro s’inserisce in un contesto più ampio, il progetto “Eravamo tutti uguali”, che ha inteso indagare sul movimento della Resistenza in quei luoghi, uscendo dal circuito tradizionale del lavoro artistico, per entrare in quello della documentazione e della testimonianza, espandendosi quindi a nuove interrelazioni espressive, e rendere omaggio a tutti i morti per la libertà.

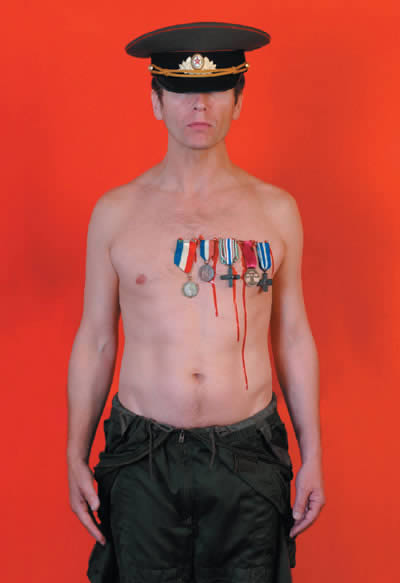

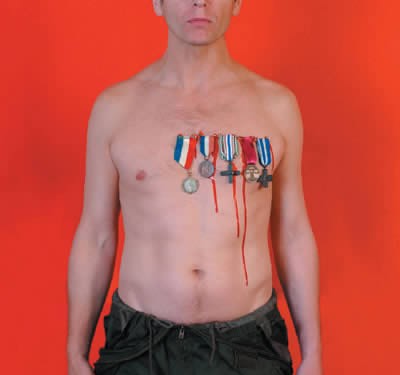

L’eco della guerra serpeggia insidiosa nelle immagini conturbanti che s’ammantano di una radicalità estrema, di Robert Gligorov. Il “Generale” appende le sue medaglie direttamente sulla carne, facendo colare il sangue; il tergicristallo della macchina deterge sangue, non pioggia (“blood rain”). Quest’ultima è divenuta l’immagine dell’intera mostra che uni.ca, nell’efficace invenzione visiva, un possibile stato di guerra con la condizione civile (la macchina non è un mezzo militare) in un unico abbraccio di violenza e morte permanenti. “Man” steso a terra, abbarbicato ad una rudimentale croce di legno insanguinata, testimonia il sacrificio della vita per ideali religiosi.

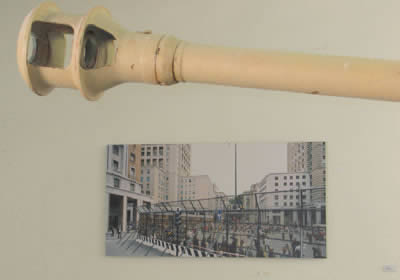

La guerra è indirettamente ricordata dagli IRWIN attraverso l’esibizione dell’assetto militare di diversi eserciti, per lo più dell’est europeo, ma anche quello di Roma, in gigantografie denominate NSK GARDA. Garanzia di difesa e sicurezza, nell’asettica disciplina che trapela dagli atteggiamenti impassibili, e che si estende persino al contesto paesistico. Potenziale, nel contempo, di esplosiva violenza organizzata. Gli IRWIN legano il loro nome ad un’antica matrice storica, al recupero e conoscenza delle proprie origini, alla propria identità e quindi ai simboli che l’hanno definita, proiettando tutto ciò nelle contraddizioni della contemporaneità, con ironia ed acuto senso critico. I documenti fotografici del G 8 di Genova del 2001 di Armin Linke ci riportano alle intense tensioni di quegli eventi: la città blindata, la zona rossa invalicabile, per la poderosa recinzione metallica, il dentro/fuori di una situazione quasi onirica, i poliziotti schierati in assetto di guerra. Sono immagini divenute ormai famose. Armin Linke osserva la realtà con occhio distaccato, cogliendone l’essenza, nella sua sospesa drammaticità, solo con i tagli azzeccati, con dilatate vedute dall’alto, secondo una prassi congeniale che lo porta a prediligere le grandi estensioni, le visioni d’insieme aperte all’infinito.

Dalibor Martinis da qualche tempo infonde nei suoi lavori una natura duale, visibile e nascosta, impiegando i testi in codice binario – utilizzati anche dai terroristi per i loro messaggi video e TV – travestiti da una forma spiazzante. L’antenna radio siglata RKO (che riconduce al film King Kong del 1933) del video “To America I say” trasmette, dopo un preambolo in alfabeto Morse, il messaggio in codice di Osama Bin Laden diramato subito dopo l’attacco alle World Trade Center Towers. Un’occasione di ribadire i tragici accadimenti del nostro tempo piegando l’ideazione e la realizzazione artistica agli attuali sistemi di comunicazione contaminati però da un’immagine che rimanda ad altri contesti.

Più da vicino Janos Sugar osserva il mondo militare nel video impregnato di ironia “The typewriter of the illitterate”. La macchina da scrivere dell’illetterato (l’artista si è allacciato ad una frase di Barry Sanders) è la mitragliatrice che con lo straordinario supporto sonoro di drums, compone l’assordante vocabolario che ogni divisa militare sa usare con grande disinvoltura. La continua trasformazione di immagini di soldati degli eserciti di tutto il mondo è attuata mediante la tecnica al computer del morphing; essi sono accomunati dall’irriducibile presenza del kalashnikov, “l’esperanto dell’aggressività” come lo definisce l’artista.

Jota Castro è schierato dalla parte del dissenso in permanenza, contro tutte le storture del mondo, la guerra in testa. Anche il suo discorso artistico affonda nei fatti quotidiani: testimonia, interviene, (sempre con le metafore dell’arte), commenta con humour immediato le macroscopiche ingiustizie, la perenne questione medioorientale, la necessità degli spostamenti dei popoli, conseguenti alle distorsioni della globalizzazione, inquadra in un pannello dal titolo “Motherfuckers never die” gli esemplari umani che lui ritiene i peggiori. “Burka-Pace”, esposto in questa mostra, è una contaminazione tra la costrizione della donna islamica e l’aspirazione alla pace, mentre “Still Life in Madrid” enfatizza in una lucida immagine fotogra.ca alcuni oggetti usati dagli attentatori di Madrid, rinvenuti sul luogo della strage.

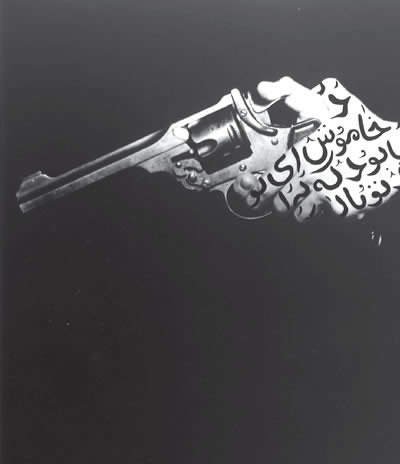

Nel quadro di una società “pubblicitaria/postumana”, nella sua costante spettacolarizzazione, Brigata Es (e il nome contiene tutto dalla disciplina militare all’irrazionalità) si è proposto di ridefinire – se possibile – il ruolo dell’artista sul principio della scomparsa dell’arte, secondo gli assiomi di Baudrillard. Nel suo percorso, abbracciato all’immaterialità tecnologica, la componente socio-politica è spesso ineludibile. La riflessione sul passaggio dall’opera all’artista, nel senso che quest’ultimo si sostituisce alla prima, comporta la simulazione di situazioni che caratterizzano la nostra società, metafore di accadimenti, parafrasi da “movie”. “Tonsura” è una video-installazione che si può leggere in tanti modi: un’allusione alla pratica militare della rasatura delle nuove reclute, costrizione omologante, riduzione di autonomia identitaria, da qualche tempo peraltro divenuta moda; in ogni caso perdita. Scivolando sul terreno della condizione femminile nel mondo, è qui ricordato anche il lavoro ormai celebre dell’iraniana (trapiantata in USA) Shirin Neshat con alcune foto della serie delle mani degli anni 1997-98: dolci mani carezzevoli che cullano bambini, ma pronte pure a impugnare la pistola, per difendere, far rispettare, ribadire un diritto negato.

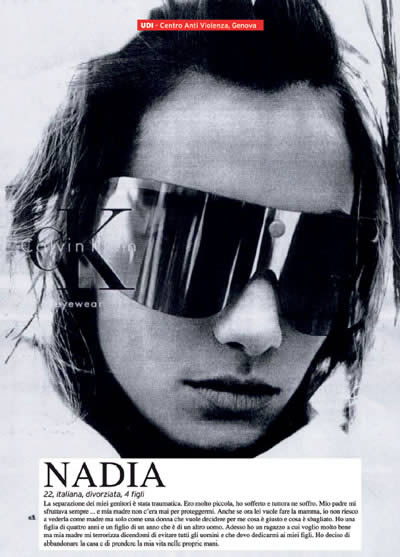

Di donne maltrattate si è occupata di recente anche la croata Sanja Ivekovic in una grande personale a Genova, città che quest’anno ha rappresentato l’anno internazionale della cultura. Della complessa operazione, che ha comportato una lunga e ben documentata ricerca da parte dell’artista, nel suo paese e in Italia, a Troubeld Times sono arrivate alcune immagini di donne con lo sguardo cancellato da una banda nera, ciascuna con la sua storia di violenza e incomprensioni, raccolta in sintesi ai piedi dell’immagine stessa. Un discorso al femminile prosegue con la sposa kossovara di Erzen Shkololli, una documentazione di cerimoniali ed usanze legate ad una terra nel cuore dei Balcani che ha conosciuto la furia distruttiva degli scontri etnici. Una testimonianza dolce e selvaggia, che può richiamare l’aura dei film di Kosturica e le sonorizzazioni di Bregovic, su cui la storia, costruita dai percorsi politici, ha lasciato i suoi segni a volte conturbanti.

Di donne si occupa anche la performance “AlphaOmega” di Liuba, della violenza della nascita e di quella della morte, perseguita sulla sedia elettrica, come esecuzione di un verdetto giudiziale. Principio e .ne accomunati dal dolore e dalla sofferenza, tuttavia costruttivo il primo, perché dà luogo alla vita, drammaticamente letale il secondo perché stronca la vita, con un atto barbaramente legalizzato.

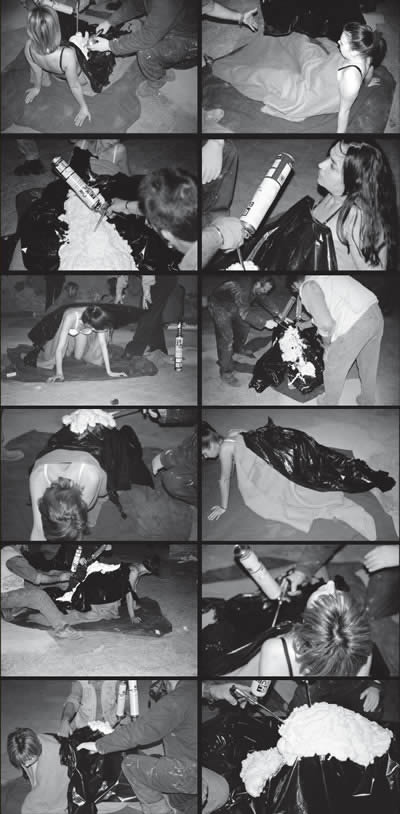

E la donna è protagonista anche del video “Espreado de poliuretano sobre 18 personas” di Santiago Sierra. Si tratta di un’azione avvenuta a Lucca nel 2002, nella chiesa sconsacrata di S. Matteo. L’artista ha impiegato 18 ragazze per lo più provenienti dall’Est – entreneuse che lavorano nei nights toscani – pagandole per la prestazione, come è accaduto in altre sue recenti azioni. Il rituale innescato – una spruzzata di poliuretano sulla vagina e sul fondo schiena di ogni ragazza, debitamente protette da plastica nera, dopo che si sono disposte sopra una coperta al centro della chiesa – chiaramente allude allo sfruttamento sessuale della donna, al potere del maschio su di lei, ad una pratica antica quanto il mondo, condensata in un’operazione .ne a se stessa, che si giusti.ca solo nell’ambito dell’arte. Si riaggancia al filone delle “azioni” dispiegate dagli anni ’60 in giù, ma si distingue per il prepotente impatto socio-politico, per la componente contrattuale e di relazione che s’instaura tra le parti chiamate in causa; entraineuses, operai che materialmente hanno eseguito l’azione, gallerista che l’ha promossa, artista, critico.

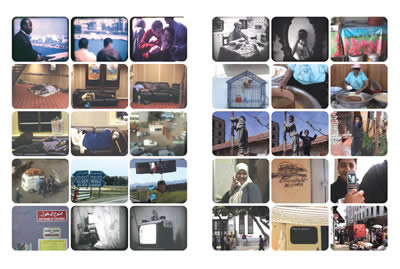

Con Katia Kameli passiamo al racconto filmico che testimonia la trasformazione di un paese (l’Algeria) e di chi lo abita, o vi ritorna ad abitare, a seguito dei mutamenti politici. L’artista segue il viaggio di un gruppo di emigranti algerini, tra cui molti giovani, che salpano da Marsiglia con la mitica nave “Mediterranée” per rientrare nel paese d’origine. Lungo il viaggio e poi ad Algeri, i passeggeri confrontano il passato con le aspettative future, formulano giudizi sui mutamenti di mentalità e di costumi, in un intreccio di diverse realtà generazionali, con particolare attenzione all’emisfero femminile, registrando la consapevolezza della trasformazione, nell’incontro di culture e pratiche esistenziali diverse.

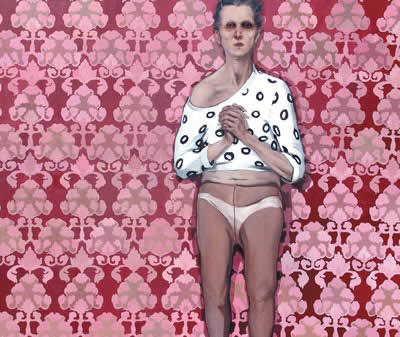

Biljana Djurdjevic s’inserisce in questo coro di espressività tecnologica con la sua raf.nata pittura che analizza con spietata intensità un’umanità o sul declino della vita, o piegata dalle debolezze della carne. La malattia, lo stato di abbandono che spesso caratterizza la vecchiaia sono crudamente puntualizzate in una pittura iperrealistica, che denuncia lo stato delle cose, enfatizzandone la visibilità. Ne risulta uno scenario umano letto attraverso una lente d’ingrandimento che ne accresce i vizi da cui è appesantito, sfociando a volte in una simbologia metaforica.

Anche Milena Dopitova affronta negli ultimi lavori il tema della vecchiaia, realtà sociale sempre più dilatata con il prolungamento della vita umana. I due diversi video di “Sixtysomething” – una complessa installazione che prevede anche delle sculture, oltre ad una serie di fotografie – documentano l’isolamento e la malinconia della gente che, raggiunta una certa soglia dell’età, dopo aver svolto tutti i ruoli che le competono in famiglia e nella società, avverte la futilità di una sopravvivenza ancorata a piccoli barlumi di apparente divertimento come i balli organizzati per persone anziane.

L’aspetto goffo dei protagonisti, lo sguardo perso nel vuoto, illustrano con efficacia la loro emarginazione, nonostante la volonterosa ricerca di socializzazione.

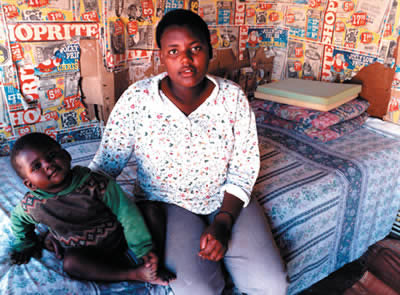

Un documento diverso ci porta il sudafricano Zwelethu Mthetwa che fotografa gli interni di povere case, tirate su con svariati residui del trash metropolitano. Il suburbio di città come Johannesburg pullula di queste precarie costruzioni che però negli interni rivelano tutta la dignità delle persone che vi abitano, specie donne e bambini, assieme alla loro modesta suppellettile tirata a lucido E’ una testimonianza, espansa nel mondo attraverso la ben riconosciuta attività artistica di Zwelethu, che nobilita un’umanità marginale e silenziosa delle “favelas” internazionali, non solo di quella africana, abbandonate dal potere al proprio destino di faticosa sopravvivenza.

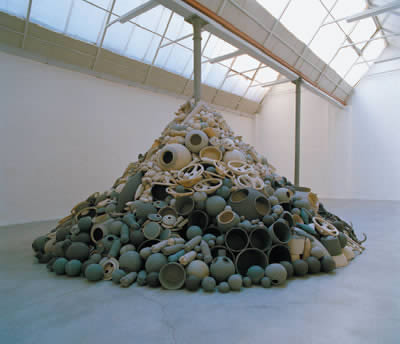

Martin Dickinger si distingue per un lavoro di accumulo. In tedesco l’artista li chiama “Halde”. Un paradigma, in un certo senso, della realtà metropolitana, accumulo produttivo, consumistico (se ne era già occupato Arman negli anni ’70, ma era rivolto soprattutto alla moltiplicazione seriale allora stigmatizzata dai benpensanti) ma anche umano, e più che mai oggi accumulo del consumato. Gli oggetti che accumula Dickinger, realizzati con la cartapesta trattata con tecniche speciali, colorati da una variegata gamma di grigi, sono i più disparati e nel loro insieme ci rappresentano. Divengono monumenti della quotidianità, tumuli dall’aspetto vagamente funereo che inghiottono la nostra vita tra vasi, parti del corpo umano, scarpe, giocattoli, volanti d’auto, palle, bombe…

Uli Von Bank Schedler s’insinua tra le pieghe degli accadimenti quotidiani – e quindi del tessuto sociale – utilizzando i giornali. L’operazione è nata con la guerra nell’ex Jugoslavia quando i giornali dedicavano pagine intere a quella tragedia. Conservare tutto diventata difficile, allora Uli per memorizzare quegli eventi ha pensato di arrotolare tutti quei fogli, in modo da ridurli, e di unirli insieme sì da formare una lunga stuoia, un tappeto di carta che racchiude nella sua trama quella della storia. L’operazione si è poi ripetuta in altre situazioni, raccogliendo in questo modo le notizie che si riferivano ad un determinato luogo dove poi veniva esposto il singolare arredo. Anche il tappeto di Troubled Times è fatto della quotidianità triestina, di quella della Regione e di quella italiana.

Heimo Wallner, assieme ai due artisti precedenti costituisce un sodalizio artistico che dura da anni. Heimo è un disegnatore formidabile, prolifico e provocatorio, può ricordare la capacità disegnativa di Gunter Brus, ma per Heimo, a differenza dell’altro artista austriaco, il disegno è l’espressione fondante della sua creatività. Il paradosso più sfrenato, tra sesso e crudeltà, pungente ironia e prassi fumettistica s’accordano in un intreccio che genera un fiume inarrestabile di immagini. Esse s’arrampicano dappertutto, sui muri come sulle palle di plastica collocate nel variegato ed infuocato contesto di Troubled Times.

Sargey Bratkov partecipa alla mostra con una personale alla Galleria LipanjePuntin. L’artista russo da sempre dà spazio a situazioni che in qualche modo rasentano il paradosso. La registrazione degli avvenimenti – scelti ovviamente in quanto passibili di letture multiple, dotati di un quid che sfocia nell’anomalia, o che conduce all’iperbole – si colora in ogni caso di un’enfasi visiva spiazzante con un’ineludibile dose d’ironia. La folla di umani che si apprestano a fruire dei miracolosi benefici del fango vulcanico mescolato ad acqua di mare in un località della Russia meridionale, nell’operazione “On a Volcano”, si trasforma, suo malgrado, in uno spettacolo tra l’assurdo e l’abnorme. Ricoperti nel corpo intero di uno spesso strato nerastro e melmoso, questi personaggi brulicanti nella mota rievocano l’aura mortifera di un girone dantesco nonostante lo slancio vitalistico da cui sono animati.

Da ultimo Ricardo Cinalli con “Piramide” compendia in una struttura ascensionale – la piramide – un ammasso umano, un groviglio di corpi che si fa simbolo – nella scrittura classica tra Rinascimento e De Chirico – dello status dell’umanità di oggi. E si fa simbolo dei contenuti di questa mostra. L’espansione demogra.ca e la compressione in spazi costretti – più metaforici che concreti – conduce all’invivibilità delle megalopoli, sia sul piano fisico che psicologico, ma contiene emblematicamente il profondo disagio, l’urto reciproco, l’alienata dimensione esistenziale di tutta l’umanità alle soglie di questo burrascoso terzo millennio.

Per una nuova architettura delle frontiere (di Predrag Matvejevic)

Predrag Matvejevic – Per una nuova architettura delle frontiere

La questione antica e sempre nuova delle frontiere riemerge in un momento decisivo della nostra storia europea, quando dieci Paesi provenienti dall’altra Europa si preparano a divenire i nuovi membri dell’Unione. Queste frontiere devono spostarsi e nello stesso tempo rimanere uguali a se stesse, sottoposte contemporaneamente a un controllo costante e rigoroso, per respingere coloro la cui presenza non è desiderata né benvenuta.

Le stesse persone che hanno vissuto, ancora ieri, tra frontiere bloccate, che dovevano superare con artifici e a volte pagando il prezzo della umiliazione, oggi si vedono chiamate a diventare i guardiani attenti di quelle barriere e a sorvegliarle rigorosamente. C’è un paradosso in questo ruolo. Non è difficile immaginare un polacco che impedisce a un russo o a un ucraino di passare attraverso il suo territorio. Ma come si comporterà un ungherese quando si presentasse davanti a lui un altro cittadino con la stessa nazionalità, che provenga dalla minoranza ungherese della Transilvania romena? O uno sloveno che, a una ventina di chilometri da Zagabria, debba fermare un croato con il quale in passato aveva condiviso una sorte comune nella ex Jugoslavia?

I vecchi particolarismi potrebbero facilmente ridisegnare le frontiere interne dell’Europa incoraggiati da ogni tipo di nazionalismo, di regionalismo, di localismo, di ”devoluzionismo” e da altre tendenze simili che si manifestano con arroganza e alle quali ogni idea di convergenza o di sintesi rimane estranea. Si tratta di ripensare, di fronte a queste tendenze irrazionali verso la divisione e la separazione, ciò che si potrebbe chiamare una nuova ”architettura della frontiera” o, perché no, una nuova etica della frontiera. La cultura avrebbe sicuramente da dire le sue parole, se non fosse così messa ai margini nella elaborazione del progetto europeo, chiamata in soccorso molto raramente o solo per liberarsi la coscienza.

Non sarebbe dunque inutile lasciare libere alcune idee che riguardano la frontiera stessa e tentare di definirla diversamente, confrontandola con le consuetudini concrete che conosciamo, vecchie e nuove. Conviene prendere nuovamente in considerazione le diverse nozioni di permeabilità delle frontiere, della accessibilità e della permessività, della fragilità, della ”doganalità” e della ”custodialità”. Alcuni di questi termini sono da inventare o da ridefinire, e ciascuno merita una riflessione particolare.

In questo contesto mi viene alla mente un antico esempio che già Tacito evocava nella introduzione della sua Germania: a fianco delle cosiddette frontiere naturali, come il Reno e il Danubio, o come alcune catene di montagne, si crea spesso una frontiera particolare imposta dalla paura reciproca. Mutuo metu diceva il vecchio storico. Questo sentimento è ben noto a una buona parte di noi, in particolare a quelli umiliati e offesi, che dovevano viverlo in passato durante la Guerra fredda. È inutile oggi parlare ancora una volta delle cortine di ferro e dei muri simili a quello di Berlino.

I processi di globalizzazione e di mondializzazione – quando non consistono semplicemente nell’imporre un nuovo ordine mondiale attraverso la conquista dei mercati – presuppongono un riesame della natura stessa della frontiera. È ben chiaro che una vera alleanza, che viene riproposta ad ogni occasione, non può essere immaginata con delle frontiere rigide o poco permeabili. Il nostro pianeta si confronta, ogni giorno con più insistenza, con le richieste che vengono da un ordine umanista, etico: la richiesta di diminuire se non di abolire i confini tra uomini con una ricchezza garantita e poveri, tra uomini ben nutriti e altri affamati, tra uomini istruiti e analfabeti.

I teorici e i protagonisti della globalizzazione sembrano dimenticare che la cultura europea aveva già conosciuto al suo interno vari movimenti a tendenza universale o, se preferiamo, mondialisti: il cosmopolitismo dei Lumi, l’ecumenismo in campo religioso, l’internazionalismo in politica, compromesso poi dal comunismo di tipo staliniano. La cultura stessa dovrebbe ricordarlo a questi teorici, se non fosse scoraggiata come appare. Queste tendenze, anche se ai nostri giorni sono minimizzate, non potranno essere sostituite da una mondializzazione a buon mercato.

Mi fermo qui, e so bene che spesso si offre una immagine ingenua, a volte ridicola, proponendo una qualunque idea morale. La nostra proposta è molto più modesta: mettere in evidenza alcune contraddizioni nel momento in cui si crea una nuova architettura del Vecchio continente.

Troubled Times (di Melita Richter Malabotta)

Melita Richter Malabotta – Troubled Times

Non potrebbe intitolarsi in modo più appropriato la mostra che il Gruppo 78 propone con la partecipazione degli artisti provenienti dall’Est Europeo e da altre parti del mondo che espongono le loro opere in uno spazio denso di significato come il Civico Museo della guerra per la pace “Diego de Henriquez”. “Troubled Times” è il sintagma che segna l’esperienza della nostra epoca, incide sulle vite di uomini e donne di interi continenti. L’espressione si presta a sfumature e interpretazioni diversificate. I dizionari suggeriscono alla parola trouble il significato di: guaio, pasticcio, difficoltà, problema, preoccupazione, disordini, conflitti, disturbi… Un ulteriore lettura, quella derivante dal vissuto di popolazioni dalle quali provengono gli stessi artisti, aggiunge significati complementari: privazioni, umiliazioni, povertà, carestie, emarginazione sociale, esclusione, odio, intolleranza, persecuzione, distruzione, fughe, esilio, migrazioni, guerre, lutti… L’elenco potrebbe essere molto più lungo e articolato. Quello che ci interessa oggi in queste terre di confine e di cui testimoniano ampiamente le opere degli autori, è la risposta a situazioni in cui sono indotti gli esseri umani soggiogati da ideologie totalizzanti e da economie assolutizzanti, è la loro reazione, la ribellione agli stati di omologazione a cui i vari ismi, artefici principali della proliferazione dei significati del concetto linguistico “troubled times”, ci vorrebbero obbligare. È la disobbedienza a simili stati e richiami.

Ciò che si profila come uno degli obbiettivi principali della mostra, è la presa di coscienza dell’artista, la sua responsabilità di fronte agli assetti sociali, politici ed esistenziali in cui egli/ella vive e non gioca più con il magico e il visionario, ma formula la denuncia e si appropria di un linguaggio artistico politicamente consapevole. Questo linguaggio è diversificato e allo stesso tempo unificatore nel pronunciare “no”; un “no” pubblico, carico di forte radicamento etico, un “no” che chiede adesioni. È il “no” allo sdoppiamento dell’uomo che ha prodotto il Golem che lo sta stritolando, è un invito alla creazione in quel senso che già in una Praga alchimista aveva pronunciato il vecchio Rabbi Ravà: “Se i giusti volessero, potrebbero essere creatori”. Ma è anche la risposta alle angoscianti domande che molte donne dei Balcani si sono poste mentre gli uomini accorrevano al fronte e mentre i nuovi patriarcati rispolverati in veste patriottica tentavano di trafiggere loro la lingua, il corpo, la mente: “Come manifestare il dissenso alla guerra in situazioni di guerra? Come reagire alla violenza socialmente strutturata e diffusa? Come sfuggire al marchio della vittima e riappropriarsi della responsabilità per il mondo in cui viviamo?” A queste domande esse hanno cercato di rispondere in maniera diversa, ognuna da un ambiente di vita distinto, di esperienza individuale e di gruppo, di cultura e di circostanze politiche, ma tutte consapevoli che il limes tra la violenza bellica e quella dei tempi di pace è molto esile. Gridando ai quattro venti lo slogan “Fuori la guerra dalla storia!” come fosse un manifesto artistico, utopico, esse aprivano gli spazi reali al dibattito e, nei tempi più bui, dal ventre infestato dell’Europa dove germogliavano le folli ideologie basate sull’esclusione dell’Altro, testimoniavano che un’altra società è possibile. Armate di un coraggio straordinario, artiste della disobbedienza, esse introducevano le piccole oasi di pace dove affermare le identità plurime.

Spesso i loro temi minimali apparivano in contrasto con “grandi imprese” e “grandi avvenimenti” legati alle patrie etniche dove la guerra faceva la parte del leone. Ma, sono proprio i temi minimali tradotti in gesti di solidarietà quelli che ri/costituiscono la normalità della vita quotidiana, i suoi molteplici intrecci e ricompongono la frantumata realtà del mondo.

È stata la guerra nell’area della ex Jugoslavia, questa vergognosa pagina della storia di un’Europa lacerata, che ha posto a noi tutti, cittadini del mondo, domande a cui tuttora si stenta dare risposte chiare e definitive: come opporsi ai nazionalismi e alle oppressive ideologie totalizzanti, alle egemonie collettiviste dello spirito, agli stati nazionali corporativi? Come procedere con la demilitarizzazione delle società e delle menti dei cittadini? Come allargare gli spazi delle società civili fondati sulla pluralità, sull’individuo portatore di dignità umane e soggetto inviolabile dei diritti civili? Come affermare la convivenza e l’interazione tra culture diverse in un contesto europeo e planetario, decisamente sempre più multietnico e interculturale? La conoscenza, l’arte e la cultura sono strumenti ideali non tanto per dare le risposte predefinite a simili quesiti, ma per aprire gli spazi del confronto, perché essi per sé rappresentano fertili espressioni dello spirito libero, soggettivo, portatore del valore solo se capace di misurarsi con l’Altro.

L’Altro nella cultura, l’Altro nella vita. La barbarie ha cercato di annientare i suoi simboli, le sue espressioni secolari, spirituali, le sue acquisizioni culturali e politiche come la sua stessa esistenza biologica. Il primo Altro dell’uomo sono gli occhi delle donne. Gli occhi delle donne sono presenti in questa mostra nel loro duplice ruolo; come sguardi delle artiste affermate e come occhi e menti di coloro che invocano un mondo diverso dove l’alterità femminile – e quella di ogni altro segno e provenienza (razza, classe, età, preferenza sessuale, dis/abilità, religione ecc.), – non sarà più privata della sua espressione pubblica, non più cancellata dallo spazio culturale, politico, storico. La loro lotta per il riconoscimento della diversità non assimilabile ci sembra identica a quella di ogni artista la cui opera afferma l’espressione della singolarità e insegue i valori di un’umanità libera da confini e frontiere.

L’incontro, lo scambio, l’interdipendenza, il pluralismo identitario, il rispecchiarsi nell’altro, la contaminazione, la sua opposizione, la mutazione, la resistenza, sono elementi indispensabili all’arte e alla cultura come alla dinamica delle società democratiche basate sull’etica della responsabilità e della convivenza. Ciò non toglie che le società multietniche e multiculturali non corrano, oggi come ieri, il rischio di essere annientate non soltanto con le armi, ma anche dalla creazione dei sistemi chiusi, divisi dai nuovi confini e dai muri invalicabili, dalle comunicazioni interrotte, dai campi minati, dagli spazi ontologicamente e realmente separati, dalle lingue e linguaggi divisi, dalle gabbie etniche, dalle vite e le menti umane sottomesse all’unica entità, quella della Nazione. Oppure, quella del Mercato. I miti etnogonici hanno spesso spezzato la complessità del pensiero e la sua espressione creativa, il mercato li ha appiattiti. L’arte, quella vera, ha saputo rifuggire questi miti, ha inseguito gli orizzonti della libertà come il suo unico spazio naturale, come le acque amniotiche dove tracciare legami, congiunzioni, passaggi.

Del resto, l’esperienza dello spazio culturale europeo non è altro che la conferma della poetica della relazione tra multiversi culturali, come direbbe Glissant. Solo essa ci acconsente di divenire creatori e di tentare di essere giusti.

Arte di Troubled Times (di Fabio Polidori)

Fabio Polidori – Arte di Troubled Times

L’arte è ingiusta. Per essenza e vocazione va contro giustizia. Per intima necessità, viola sistematicamente regole e ordini. Non si dà evento artistico senza un lavoro di forzatura, di effrazione di norme e codici, quelli secondo cui si ordinano i rapporti umani. Da qui, da sempre, il senso dell’arte e del suo fare: la sua capacità di modificare e sovvertire visioni del mondo, di produrre slogature nel tempo e nelle epoche, di infliggere distorsioni alla sensibilità. Da qui anche, però, la sua responsabilità: la responsabilità del fare artistico che mette in opera tutto quanto è dissonanza, contrasto, urto per le consuetudini, nostre e legittime. Una responsabilità che è anche tragica (ma si dà responsabilità che non lo sia?) perché richiama a un agire assoluto, sciolto da qualsiasi riferimento ad altre e diverse consuetudini, ad altre e diverse legittimità, un agire che fa – ma senza prospettive di altri e diversi ordini, supposti migliori e da introdurre per sostituzione –, che semplicemente fa, opera. Questa è la responsabilità tragica da cui discende, direttamente, l’infinita forza critica del fare arte.

Arte e critica, nel loro profilo essenziale, sono la stessa cosa, il medesimo agire che non prefigura soluzioni, che non segnala alternative, che non formula proposte innovative ma che, piuttosto, rivendica per sé solo il compito di un altro vedere, di un far vedere altro. Senza per questo avanzare la pretesa di modificare ciò che si vede, il cosiddetto esistente, ma con la determinazione di, semplicemente, innescare una deriva, indurre una vibrazione, introdurre una impertinenza nello sguardo; produrre insomma una disassuefazione al riconoscimento di ciò che è, di ciò che è come è solo perché lo si è già sempre visto (o dovuto vedere) come appunto è. Così, non basta che la preoccupante e preoccupata agitazione – giusta alcuni significati del «troubled» – di questi tempi, che sono i nostri, si rifletta, più o meno meccanica e inerte, in ciò che l’opera dà a vedere.

Qui l’opera è chiamata a inquietare la tranquilla digestione con cui gli sguardi, i nostri sguardi, assimilano, sotto forma di immagini, realtà inconcepibili. Non inconcepibili perché violente, strazianti, commoventi, macabre, forse anche entusiasmanti; ma inconcepibili perché – che lo vogliamo o no – esibiscono l’ordine del mondo: le sue regole, le sue leggi, la sua giustizia. Un ordine, quello del mondo, che coincide con (meglio ancora: che è) l’ordine del nostro sguardo. Persino quando il giudizio è di radicale condanna, persino nella più irriducibilmente contraria presa di posizione civile e politica, ciò che è in questione e che si giudica, l’elemento giudicato, insomma il dato, è sempre fuori discussione: anzitutto le cose stanno così come le vediamo; poi, possono andarci bene o male. Da quel sempre troppo rapido e affrettato «così» l’arte ha la responsabilità di metterci in guardia; la responsabilità di introdurre rallentamenti o accelerazioni, smarcamenti dall’ineluttabilità del consueto, ha la responsabilità di frenare l’erosione della sensibilità.

Responsabilità, si diceva, infinita e senza mandato che risponde solo a se stessa, senza contenuto si potrebbe dire; responsabilità del fare arte in cui solo .no a un certo punto va distinto chi fa da chi guarda, chi dà a vedere e chi vede attraverso la trasformazione di sguardi in opera; responsabilità, infine, di segnare i volti ingiusti della giustizia, di manifestare le invisibili crudeltà dell’ordine e della legge, dell’uguaglianza e del diritto, di amplificare l’urgenza dell’inaudito, del non visto, dell’escluso, dell’implicita miseria di ogni ricchezza, dell’implicita morte di ogni vita. Questa la necessaria ingiustizia del fare dell’arte e dell’opera, l’inassimilabilità a qualsiasi discorso edificante, l’irriducibilità a strumento di qualsiasi istanza «giusta» o «legittima», sempre alimentata da sofferenza, esclusione, disagio. In questo senso, forse, non si dà gesto più politico di quello radicalmente impolitico, di quel gesto che si tiene a distanza da ogni tipo di ordine, di ragione, che si esclude dalla comunità per (tentare di) dare voce a tutto ciò che ordine, ragione, comunità escludono. E che solo uno sguardo, per forza ingiusto e per ciò capace di entrare e sostenersi nella zone cieche della giustizia, può dare a vedere.

Troubled Times (by Maria Campitelli)

Maria Campitelli – Troubled Times

These are difficult times: after September 11, 2001 the world has changed. Terror, driven by cultural, religious, economic and social differences, as well as sinister material interests, is spreading everywhere and conditioning our lives. But other radical transformations are also causing upheaval around the world, from globalisation, with its myriad, unforeseeable interactions in the most disparate areas of the planet, to the technological invasion, mass migrations, the parcelling up of every type of structure, whether urban or territorial, and even the system of war which has become a form of generalised guerrilla warfare. The state of war is one of the factors that most unsettles and afflicts humanity, despite the universal desire for peace. A continuous negative conflict seems to be in course throughout the streets of the world (in Europe, we need only think of the Balkans and the immense difficulties in rebuilding the countries involved in previous conflicts) and Goya’s ‘sleep of reason’ continues to generate menacing monsters, undermining the order of things and threatening the balance of the ecosystem.

The condition of women, and not only in Islamic countries, also represents a fundamental node in this period of negative conjunctions, notwithstanding the emancipation promoted and achieved in the feminist battles of the western countries. And then there is the abuse of minors, innocent victims of a generalised violence that seems to be the distinguishing feature of this time out of joint; social-economic inequality, with only 20% of the world’s population enjoying a certain affluence while the vast majority goes hungry and does not even have access to basic necessities such as water; injustice; the oligarchic concentration of power which ignores the will of the masses… and we could go on and on.

Troubled Times, in sensing this general feeling of malaise and distress, seeks to verify how the artist reacts to the continuous imbalances and permanent innovation in certain areas, the difficulties in adjusting and finding new forms of stability which result, and the existential precariousness which is everywhere evident in this historical moment.

How are artists reacting to this situation, what is their responsibility and the ethical foundation which guides their work with respect to these epoch-making changes which are sweeping the planet? The artist is per sé revolutionary, as the history of the avant-garde demonstrates. The artist does not bow to the dictates of power unless forced to, and reacts against the restraints and structures of any regime with provocation, irony, criticism and satire, while denouncing the powers that be either directly or implicit sense of freedom which has always distinguished Art. The most recent major international art exhibitions, such as the Biennials (in Venice and elsewhere) have provided numerous examples of artists who have taken a stance on social-cultural issues (often in conjunction with other creative/ productive forces) while some have also offered alternatives to the present state of malaise and conflict.

The latest Venice Biennial, in particular, with its chaotic format and its continuous openness to documentary rather than to more traditional work, provided ample confirmation of this approach. This was especially true in the section entitled ‘Urgency Zone’, which dealt directly with the deconstruction and reorganisation taking place at various levels in society today.

As the curator of the section, Hou Hanrou, pointed out, the urgent need to dismantle obsolete conjunctions and rapidly reconstruct them in limited autonomous areas (which are often Asian urban agglomerates), indicates the need for piecemeal change in a chaotic context, in the interaction between resistance and innovation. Jota Castro, an artist who also appears in Troubled Times, participated in the Biennial with her “Survival guide for demonstrators”. Thus artists, like pacifists and certain political movements that eschew the mainstream political parties, also follow their own path of dissent, utilising the disruptive and privileged power of invention, of a free expression which uses the most advanced technologies together with more traditional means and approaches.

Wherever freedom is trammelled, or there is the possibility of a regimented conditioning, Art has always rebelled, seeking to eliminate borders and restrictions and affirming its firm belief in the need for openness and not closure, especially in the area of communication, which is its very essence.

The artists of Troubled Times denounce, underscore and expose situations, often without comment given that the works speak for themselves. Their approaches vary from analysis, to metaphors and irony, and even the ludic, as in “The Magic War in a Wonderful World” by Massimo Poldelmengo, with its reference to Louis Armstrong and cinematographic citations. The chromatic splendour of the toy soldiers and their weaponry, with the aid of a sophisticated audio-visual alchemy transform the negativity of war into a delicate and spectacular fair.

In a completely different approach, we find the sublimation of death in the video “Cleaning the Mirror” by Marina Abramovic. In the pulsing rhythm of the artist’s breath and the steady progressive merging of her face with a skull that bears down upon it, she anticipates and sums up the agonising and obsessive, macabre and realistic meaning of “Balcan Baroque”, her unforgettable performance at the ’97 Biennial, which provided an emblematic image for the Balkans war.

War is one of the themes around which the exhibition revolves and is interpreted by the participating artists in a variety of ways. For the Iraqui Al Fadhil it is concentrated in the blow-up of a single bullet, elongated and elegant, a polished, lucidly designed object that responds perfectly to the historical axiom “Form follows function”.

Another projectile, in video-projection, rotates in.nitely accompanied by a spoken text, meaningful as it is heartbreaking. This work provides an allusive and inevitable link with Marco Vaglieri’s “The Seven Turningpoints”: seven copies of photographs that associate images of relicts from WWI and poetic thoughts which, in a temporal sequence based on the days of the week and the Stations of the Cross, denounce the fundamental concepts of loss and disorder generated by war’s destructive power. The video is the first part of “The Time Needed”, a bitter reflection on the essence of war through the analysis of the relicts of remote conflicts which were found in the actual locations (in this case, the Karst) where those tragic events originally took place.

Memory, evocation, a calm and contained narrative rhythm, penetration into the past in order to project it into the present: all these elements can be found in the video “Casa Gatti 44-03” by Gianmaria Conti. The video reconstructs a terrible Nazi-Fascist retaliation against a group of partisans who had taken refuge in Casa Gatti, near Modena, through the simple expedient of documenting the exterior and interior (which has remained virtually unchanged since 1944) of the house where the massacre took place. Only some distant gunshots at the end recall the terrible violence perpetrated at that time. This work forms part of a larger project, “We were all equal”, which sought to investigate the Resistance in that area of Italy. By moving beyond the traditional scope of artistic production and entering the area of documentation and testimony, the project created new expressive inter-relations while also paying homage to all of those who died in the name of freedom.

The echo of war also insinuates itself into Robert Gligorov’s extreme and disturbing images. The “General” pins his medals directly onto his flesh, making his blood run; in a second image, the windshield wipers of a car sweep away blood instead of rain (“Blood Rain”). This work has been chosen as the keynote image for the entire exhibition because it unifies, in an extremely effective visual invention, a possible state of war with a peacetime, civilian condition (the car is, in fact, not a military vehicle), creating a single embrace of violence and death. Another image, “Man”, depicts a body affixed to a crude cross of blood-stained wood lying on the ground, stark testimony to the countless lives sacrificed in the name of religious ideals.

War is recalled indirectly by IRWIN in the blow-up “NSK GARDA”, which depicts the military units of mostly Eastern European armies (though Rome is also present). These figures are the protectors of national security, adepts of an ascetic discipline which is evident in the impassive poses, and that even involves the landscape; but at the same time they represent the potential of organised violence, ready to explode. The artists who make up IRWIN links their name to an ancient historical matrix, the recovery and knowledge of their own origins and identity, and thus to the symbols that have defined it, projecting the whole into the contradictions of the present-day with irony and an acute critical sense.

The photographic documentation of the G8 in Genoa in 2001 by Armin Linke takes us back to the incredible tensions of those events: the fortified city, the inviolable ‘red zone’ with its heavy metal barrier, the inside/outside of an almost dreamlike situation, and the police drawn up in battle array. Images which have since become celebrated. Armin Linke observes events with detachment, capturing the essence, in its dramatic suspension, with precise cuts and framings and wide-angle views from above, in keeping with his predilection for vast extensions and overviews open to infinity.

For some time now, Dalibor Martinis works have had a dual nature, both manifest and hidden, thanks the use of binary codes (a technique also used by terrorists in their video and television messages) disguised within a form that disorients. The RKO radio antenna (a citation from the 1933 .lm, King Kong ) in the video “To America I say” transmits, after a preamble in Morse code, Osama Bin Laden’s coded message after the attack against the World Trade Center Towers. In this repetition of the tragic events of our time, the artistic concept and realisation is made to conform to current systems of communication while being contaminated by an image which refers to a different context.

Closer to home, Janos Sugar observes the world of militarism in a video impregnated with irony “The Typewriter of the Illiterate”. The title (which cites the famous phrase by Barry Sanders) refers to the machine gun, and with the aid of drums composes the deafening vocabulary that any soldier, regardless of his uniform, knows how to use with great nonchalance. By means of computer morphing, the images of soldiers from armies from around the world are continually transformed and associated with the ineluctable presence of the kalashnikov, the ‘Esperanto of aggressiveness’ as the artist calls it, coining a phrase of his own.

Jota Castro’s position is one of permanent dissent against all of the distortions of the world, with war being the greatest distortion of all. His artistic discourse is rooted in the day to day as he documents, intervenes (always with the metaphor of art) and comments with a reflexive humour the extraordinary injustices that exists, from the eternal issue of the Mid- East to the mass migrations resulting from the upheavals caused by globalisation, framing in a panel entitled “Motherfuckers Never Die” his own Top 10 of the world’s worst people. The exhibition includes “Burka-Pace”, a contamination between the constrictions of Islamic women and the desire for peace, while “Still Life in Madrid” dwells, in a lucid photographic image, on some of the objects used by the terrorists in Madrid which were found at the sites of the attacks.

Within the framework of a “post-human advertising agency’ and a constant love of spectacle, Brigata Es (a name which includes both the military ‘brigade’ and the irrationality of the Id) has sought to redefine – if possible – the artist’s role based on the principle of the disappearance of art, in accordance with Baudrillard’s axiom. In Brigata’s itinerary, which is wrapped in a technological immateriality, the social-political component is often unavoidable, while the reflection on this passage in his work (in the sense that this component has replaced what came before) results in the simulation of situations that characterise our society, metaphors of events, cinematic paraphrases. ‘Tonsure’ is a video installation which can be interpreted in various ways, and alludes to the military custom of shaving the heads of new recruits (a ‘look’ which has also become fashionable in civilian life), in order to replace an autonomous identity with one which anonymous and uniform and which, in any case, constitutes a ritual that is emblematic of loss.

As regards the condition of women in the world, we should recall the, by now, celebrated work from 1997-98 by the Iranian transplanted to the USA Shirin Neshat: photos of a series of hands caressing children but which are also ready to grip a pistol in order to defend a right which has been denied.

The Croatian artist Sanja Ivekovic has also recently dealt with the issue of abused women in a large one-woman show in Genoa, the city which this year hosts the international year of culture. From this complex operation, which required extensive research in her native country and in Italy, Troubled Times presents a number of images of women with a black strip over the eyes, each with her story of violence and incomprehension which is summarised at the base of the image. This feminine discourse continues with the bride from Kossova by Erzen Shkololli, a work which documents the ceremonies and customs of this region in the heart of the Balkans that has known the destructive fury of ethnic conflict. Shkololli offers a gentle and savage testimony, recalling Kosturica’s films and Bregovic’s soundtracks, works which have been profoundly marked and at times contorted and distorted by the political twistings and turnings of History.

The performance “AlphaOmega” by Liuba also deals with women, focussing on violence as a constant from birth to legal execution in the electric chair. A beginning and end joined by the common denominator of pain and suffering, constructive in the first instance because giving life, dramatically lethal in the second because cutting short a life with a barbaric, albeit legal act.

Woman is also the protagonist of the video ‘Espreado de poliuretano sobre 18 personas’ by Santiago Sierra, which records an event performed in Lucca, in 2002, in the desanctified church of S. Matteo. The video utilises 18 young women, mostly from Eastern Europe, who work as hostesses in Tuscan nightclubs, and who were paid by the artist for their services, following a practice used in other recent works. The ritual, which consisted of a bit of polyurethane sprayed on the vagina and lower back of each girl (protected by black plastic), and with all the young women arranged on a bedspread at the centre of the church, clearly alludes to the sexual exploitation of women and male domination, and to the world’s oldest profession, condensed in an operation which is an end to itself and which is justified only in the context of Art. We are in the realm of ‘actions’, a mainstay of contemporary art since the ‘60’s, but which in this instance is distinguished by its powerful social-political impact, and the contractual and relational component among the parties involved: the hostesses who performed the action, the gallery owner who promoted it, the artist and the critic.

With Katia Kameli we move on to a filmic story which testifies as to the transformation of a country (Algeria) and those who live there, or return to live there, after a series of political changes. The artist follows the journey of a group of Algerian emigrants, many quite young, who sail from Marseilles on the legendary ship the “Mediterranée” in order to return to their native country. During the voyage and later in Algiers, the passengers compare the past with their future expectations, and discuss the changes that have taken place in mentality and customs. What results is in an interweaving of different generational realities, with a special focus on women, and the record of the varying degrees of awareness of the transformation that has taken place, in the encounter of cultures and practices which are existentially diverse.

Biljana Djurdjevic takes her place in this chorus of technological expression with her refined painting that analyses with pitiless intensity a humanity which is either in decline or oppressed by the debility of the flesh. Illness and the state of abandonment which often characterises old age are crudely detailed in a hyper-realistic painting that denounces the state of things, stressing their visibility. What results is a human scenario seen through a lens that magnifies the flaws and defects that burden it, and which at times makes a metaphorical use of symbols.

In her latest works, Milena Dopitova also deals with the theme of old age, a social reality which has become increasingly relevant with the lengthening of the average human life span. The two videos of “Sixtysomething” – a complex installation that also includes sculpture and photographs – documents the isolation and melancholy of older people who no longer have a family or social role, stressing the futility of a survival anchored to little glimmers of apparent diversion such as the dances organised for the elderly. The awkward appearance of the participants and their empty stares confirm their marginalisation, even as they are intent upon socialisation.

The South African Zwelethu Mthetwa instead documents the interiors of shacks constructed from the trash and detritus of major cities. The peripheries of cities like Johannesburg swarm with these precarious constructions the interiors of which, however, reveal the dignity of those who live there, especially the women and children, through their modest and brightly polished furnishings. Zwelthu’s internationally known photographs are documents which enoble the silent and marginal inhabitants of the “bidonvilles”, not only in Africa but around the world, a humanity which has been abandoned by the powers that be to their daily struggle for survival.

Martin Dickinger is noted for his “accumulations” (in German, the artist calls them Halde). In a certain sense, they are a paradigm of metropolitan reality, productive and consumer oriented (one of Arman’s themes in the ‘70’s, though primarily through the use of the serial multiplication stigmatised by the right-thinking) but also human, and today more than ever the accumulation of what is consumed. The objects which Dickinger accumulates, which are made of specially treated paper maché and coloured with varying shades of grey, because of their extraordinary diversity, when taken together can be seen to represent who we are. They become monuments to the quotidian, vaguely reminiscent of burial mounds that swallow our lives amid vases, human body parts, shoes, toys, steering wheels, balls, bombs… Uli Von Bank Schedler works her way into the interstices of daily events – and thus of the social fabric – using newspapers. This operation began with the war in the former Yugoslavia, when newspapers dedicated entire pages to that tragedy. Because it was difficult to conserve them all, Uli began to reduce the volume of the pages by rolling them up, and then wove them together in a sort of long reed-mat, a paper carpet which includes history and memory in its weave. The operation was then repeated for other situations, with the culling of news items that referred to the place where this “mat” would then be displayed. In fact, the mat for Troubled Times includes newspapers from Trieste, the Region of Friuli Venezia Giulia and from the rest of Italy.

Together with the two previous artists, Heimo Wallner has formed an artistic partnership that has lasted for years. Heimo is a formidable draughtsman, both prolific and provocative. Contrary to another Austrian artist, Gunter Brus, whose work is similar, for Heimo drawing is the fundamental expression of his creativity. His works exhibit an unbridled paradox, in which sex and cruelty, pungent irony and comic-book techniques merge in a resistless .ow of images. Like tendrils of a vine they climb up everywhere, on the walls and plastic balls located throughout the variegated and inflamed setting of Troubled Times.

Sargey Bratkov participates in the exhibition with a one-man show at the LipanjePuntin Gallery. The Russian artist has always had a predilection for situations which are in some way paradoxical. He records events which are chosen because susceptible to multiple interpretations and endowed with a quid that leads to anomaly or hyperbole and which, in any case, are tinged with disorienting visual accents and inevitable doses of irony. In the operation ‘On a Vulcano’, the human swarm which gathers to benefit from the miraculous properties of volcanic mud mixed with seawater somewhere in southern Russia, is transformed, almost in spite of itself, into a spectacle which is both absurd and abnormal. Their bodies covered by a thick coat of black slime, these figures wallowing in the mud evoke the underworld aura of one of Dante’s circles of Hell, notwithstanding the vitalistic impulse which animates them.

Finally, Ricardo Cinalli‘s ‘Pyramid’ summarises in an ascensional structure – the pyramid – a human heap, a mass of bodies that symbolises, as in the classic texts from the Renaissance to De Chirico, the state of humanity today, while also providing a symbol for this exhibition. The demographic expansion and compression in restricted spaces – more metaphorical than real – leads to the inevitability of the megalopolis, on both the physical and psychological plane, while also containing, and emblematically so, the profound uneasiness, the reciprocal jostling and elbowing, the alienated existential dimension of all humanity on the threshold of this tempestuous Third Millenium.

For a new architecture of borders (by Predrag Matvejevic)

Predrag Matvejevic – For a new architecture of borders

The ancient but always actual issue of borders reappears in a defining moment of European history, as ten Countries from the ‘other’ Europe prepare to become new members of the EU. The borders in question must be shifted and yet remain intact, while also being subjected to a constant and strict surveillance in order to keep out the undesired and the unwelcome. Those who only yesterday were living behind closed borders which could only be crossed by means of stratagems, and often at the cost of humiliations, are now called upon to become the strict and vigilant guardians of those same frontiers. This role is paradoxical. It’s not hard to imagine a Pole who prevents a Russian or Ukrainian from entering his country. But how will a Hungarian behave when someone of the same nationality who is a member of the Hungarian minority in Rumenian Transylvania appears before him? Or a Slovene who, twenty kilometres from Zagabria, has to stop a Croatian with whom he only recently shared a common destiny in the former Yugoslavia?

The old ‘particularisms’ could easily redraw the internal borders of Europe, encouraged by every kind of nationalism, regionalism and localism, and by forms of ‘devolution’ and similar trends which manifest themselves with arrogance and refuse any idea of convergence or synthesis. Faced with these irrational movements towards division and separation, we must rethink what can be called a new ‘border architecture’ or, why not, a new border ethic. Culture could certainly play a role here, if it were not so sidelined in the creation of the European project, where it is called on for help only rarely and only in order to salve the collective conscience.

It might therefore not be an entirely fruitless exercise to leave a number of ideas concerning frontiers free and open, and to try to define them differently, comparing them with the real tangible customs which we are all familiar with, both old and new. We must reconsider the various notions of the permeability of borders, their accessibility and permissiveness and fragility, the concepts of ‘border controls’ and ‘custodianship’. Some of these terms need to be invented or be redefined, and each merits a specific attention.

This issue leads me to recollect an example cited by Tacitus in his introduction to the Germanic peoples: alongside the so-called natural frontiers such as the Rhine and the Danube, or certain mountain ranges, there are often frontiers which are imposed by mutual fear. Mutuo metu, as the ancient historian put it. This concept is well known to the majority of us, especially to those who experienced it during the Cold War with humiliation and offence. Today, it would be pointless to once again speak of the Iron Curtain or of barriers like the Berlin Wall.

The processes of globalisation and universalisation – when they do not simply consist in imposing a new world order through the conquest of markets – presupposes a re-examination of the very nature of borders. It is quite clear that a true alliance, which is touted on every possible occasion, is inconceivable with rigid and nearly impermeable frontiers. Each day, and with increasing insistence, our planet has to deal with requests of a humanistic and ethical order: the request to reduce if not eliminate the borders between people with a guaranteed affluence and people who are poor, between those who are well nourished and those who are hungry or starving, between the educated and the illiterate. The theoreticians and protagonists of globalisation seem to forget that European culture has already known various universal or, if one prefers, ‘global’ movements: the cosmopolitanism of the Enlightenment, religious ecumenism and political internationalism, which was subsequently compromised by Stalinism. The world of culture, if it were not as discouraged as it appears to be, should remind our theoreticians of this fact. These trends, even if they are currently minimised, cannot be substituted by globalisation on the cheap. I’ll stop here, knowing full well that often one appears ingenuous and, at times, even ridiculous when proposing some moral idea. Our purpose is much more modest: we simply wish to point out a number of contradictions at a time when the new architecture of the Old Continent is being established.

Troubled Times (by Melita Richter Malabotta)

Melita Richter Malabotta – Troubled Times

No title could be more appropriate than the one which Gruppo 78 has chosen for this exhibition which will include artists from Eastern Europe and other countries around the world and which will be presented in a location dense with meaning: the “Diego de Henriquez” Museum of War and Peace. “Troubled Times” is the syntagma which encapsulates the experience of the present era, which is impacting on the lives of the men and women of entire continents. This expression lends itself to different interpretations and shades of meaning. In the dictionary, ‘trouble’ is defined as:: misfortune, mess, difficulty, problem, worry, disorder, conflict, disturbance… However, if we delve still further we can add some additional meanings that derive from the experiences of the countries of origin of the artists involved: deprivation, humiliation, famine, social marginalisation, exclusion, intolerance, persecution, destruction, exile, migration, war, grief… And the list could go on and on. What concerns us today in this border region and finds ample representation in the works of these artists, is the response to situations which human beings are forced to live in due to totalising ideologies and absolutist economies, and their reaction, their rebellion against the state of uniformity which the various ‘isms’, the prime artificers of the proliferation of the meanings of the linguistic concept “troubled times”, would like to impose upon them. A response which can be seen as disobedience to such situations and imperatives.

One of the main aims of the exhibition is the awareness and responsibility of artists with respect to the social, political and existential situations in which they live, such that the artist no longer works with the visionary or magical but formulates a ‘j’accuse’ and appropriates an artistic language which is politically aware. While this language is diversified it is also unified in its saying ‘no’; a ‘no’ which is public, charged with and rooted in ethics, and which calls on others to join their voices to its own. It is the ‘no’ of the doubling of Man that has produced the Golem that is crushing humanity, the invitation to creation in the sense in which in an alchemist Prague the old Rabbi Ravà declared: ‘If the righteous so desire, they can become creators’. But it is also the reply to the anguished questions which many women in the Balkans asked themselves while the men rushed off to the front and while the new patriarchs, recycled in patriotic trappings, tried to nail down their tongues, their bodies and their minds: “How manifest one’s opposition to war in time of war? How react to socially structured and diffused violence? How avoid being branded as a victim and once again take responsibility for the world in which we live?” They tried to respond to these questions in different ways, each from a different situation, a different individual and collective experience, a different culture and set of political circumstances, but all with the awareness that the limes between the violence of war and that of peace is very fine indeed. They shouted from the rooftops the following slogan ‘History without wars!’ as if it were an artistic, utopian manifesto, they opened real spaces to debate and, in the darkest hour, in the infested underbelly of Europe where mad ideologies based on the exclusion of the Other were slouching to be born, they demonstrated that another society was possible. Armed with an extraordinary courage, artists of disobedience, they created little oases of peace where a multiplicity of identities could be affirmed.

Often their minimal themes appeared in contrast with the “great enterprises” and “great events” of the ethnic homelands where war had the lion’s share. But it is precisely the minimal which, when translated into acts of solidarity, re/constructs the normality of daily life, its myriad intertwinings that recompose the fragmented reality of the world.

It was the war in the area of the former Yugoslavia, that shameful page in the history of a lacerated Europe, which made all of us as citizens of the world face a series of questions which have yet to find a clear and definitive answer: how can we oppose nationalisms and oppressive and totalising ideologies, collectivist hegemonies of the spirit, corporate national states? How proceed with the demilitarisation of society and the minds of the citizenry? How expand the spaces of a civil society founded on pluralism and the individual as someone who possesses human dignity and inviolable rights? How affirm the coexistence and interaction among different cultures in a European and international context that is increasingly multiethnic and intercultural?

Knowledge, art and culture are ideal tools which, instead of offering predefined answers to such questions, open areas for comparison, areas that in themselves represent fertile expressions of the free, subjective spirit, a spirit which has value only if it is able to measure itself against the Other.

The Other in cultural terms, and the Other in life. The various barbarisms have tried to destroy its symbols, its age-old spiritual expressions, its cultural and political gains and its very existence as a living being. The men, the Other is to be found in the eyes of women. The eyes of women are present in this exhibition in their dual role: as the way noted artists see things and as the eyes and minds of those who invoke a different world where female otherness – and that of any other kind or origin (race, class, age, sexual preference, dis/ability, religion, etc.) – will no longer be deprived of its public expression, or cancelled from culture, politics and history. Their battle for the recognition of a diversity that cannot be assimilated appears as identical to that of every artist whose work affirms the expression of the singular and unique and pursues the values of a humanity freed of borders and frontiers.

Encounter, exchange, interdependence, the plurality of identities, the reflection of ourselves in the other, contamination, opposition, mutation and resistance are all indispensable elements for Art and culture, as they are for the dynamic of democratic societies based on the ethic of responsibility and coexistence. But this does not alter the fact that multiethnic and multicultural societies, now as in the past, not only risk being destroyed by arms, but also by the creation of closed systems, divided by new borders and insuperable walls, by minefields, by spaces which are separate in both real and ontological terms, by divided tongues and languages, ethnic cages, and by human lives and minds reduced to a single entity, that of the Nation. Or the Economy. The complexity of thought and its creative expression has often been dashed by ethnogenic or racial myths, and levelled by the marketplace. Art, true art, has always known how to free itself from these myths, following the horizon of freedom as its only natural space and scope, as a sort of amniotic fluid in which to trace ties, conjunctions, passages.

In any case, and as Glissant tells us, the experience of European culture is nothing other than the confirmation of the poetics of relations among multifaceted cultures. Ultimately, it is this, and only this which permits us to become creators and try to be just.

Art for Troubled Times (by Fabio Polidori)

Fabio Polidori – Art for Troubled Times

Art is unjust. Due to both its essence and vocation it is contrary to justice. By an intimate Necessity, it systematically violates rules and order. There is no artistic event without a work of stretching or breaking the norms and codes which order human relations. This has always been the meaning of Art and its action: its ability to modify and subvert a vision of the world, to produce dislocations in different times and historical periods, and inflict distortions of sensibility. But this is also the source of its responsibility, the responsibility of the artistic act which utilises all forms of dissonance, anything which opposes and administers shocks to the habitual and customary (what is ours and legitimate).

A responsibility which is also tragic (but isn’t all responsibility tragic?) because it calls for an absolute form of action, free of any reference to other and different practices or customs, to other and diverse forms of legitimacy, an action carried out – but without being projected towards other or different forms of order, without a better premised and to be introduced by substitution – which simply does, works . From this tragic responsibility stems the infinite critical force of making art. Art and criticism, in their essential profile, are the same thing, the same form of action that does not offer solutions, or indicate alternatives or formulate innovative proposals, but only sets itself the task of another way of seeing, of seeing something else. And without the presumption of modifying what is seen, the so-called existent, but simply in order to trigger a form of drift, induce a vibration, introduce an impertinence into our way of seeing. In short, it wishes to de-habituate the recognition of what is, of that which is what it is only because it has always been seen (or has always had to be seen) as such. Therefore, it is not enough that the worrying and worried agitation (two of the meanings of ‘troubled’) of this, our present time, is reflected more or less mechanically and inertly in what the work shows us. Here, the work is called upon to disturb the peaceful digestion by which the eyes, our eyes, assimilate, in the form of images, inconceivable realities. Not inconceivable because violent, distressing, moving, macabre and perhaps even exciting; but inconceivable because – whether we want them to or not – they show the order of the world: its rules, laws and justice. An order, that of the world, which coincides with (or better: which is) the order of our way of seeing. Even when the judgement is one of radical condemnation, even in the most irreducible civil and political opposition, what is in question and what is judged, the element which is judged, in short: the given, is always beyond discussion. First and foremost things are as we see them, and then we can decide whether we agree or disagree, consider this positive or negative.